Revisiting Postgres -1

A series of articles about stuff I'm reading in Postgres

In college, we were taught about MySQL. It was in fact, the First Database I ever even tried. Since then, I’ve tried using a lot of databases, but MySQL holds a special place in my mind, simply because it was the First one I learnt about. So for that reason, I even seem to have conflated it as one of the earliest databases to have been created.

But it turns out, that the origin of Postgres pre-dates MySQL and many other Relational Database systems! So, given this seniority.. and my interest in all things data, I thought I will embark on this journey of understanding in depth, one of the oldest databases to have been created - Postgres.

Now, there are different ways in which to learn something these days. We are spoilt for choice, in fact. The documentation, sheer googling, Youtube videos, blogs by thousands of people who have found themselves bitten by the curiosity bugs before me, and now ChatGPT and other Large Language Model clients. The problem ironically is, that given this vast buffet of choices, it sometimes can get paralyzing to try and start learning something new. But I’m going to try.

Now almost every blog starts off with “How to Install Postgres”. So have I -

But let’s go further this time.

This particular chapter is about Indexes. An index is basically a lookup mechanism. If you think about it from the point-of-view of say, a textbook, an index tells us which chapter falls on which page, so as to make it easy to access that chapter without having to Scan the whole book.

This is what Indexes or Indices do for a database.

Let’s try this out for ourselves and see what the difference is if we use an Index.

The way to compare this would be to backtrack and notice from the example that, what an index does is to make “lookups” faster.

So let’s do just that - Look up some value from a table.

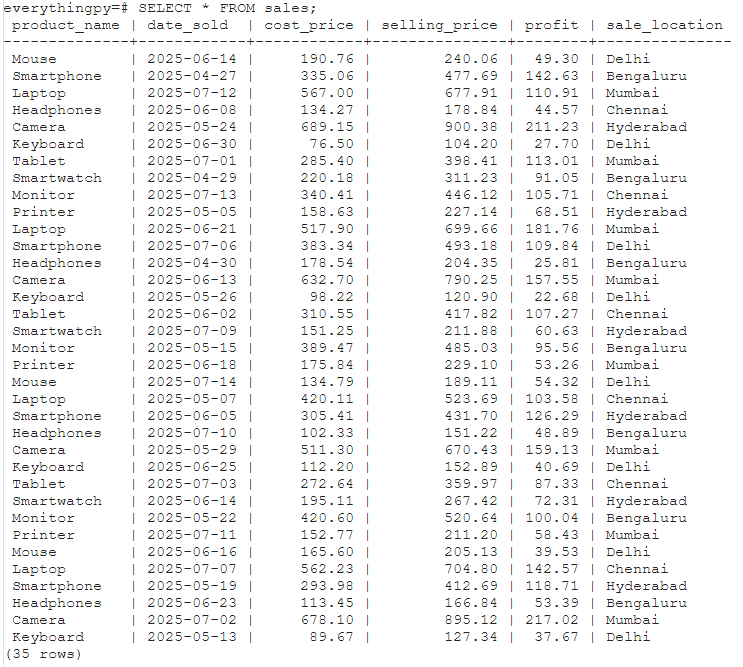

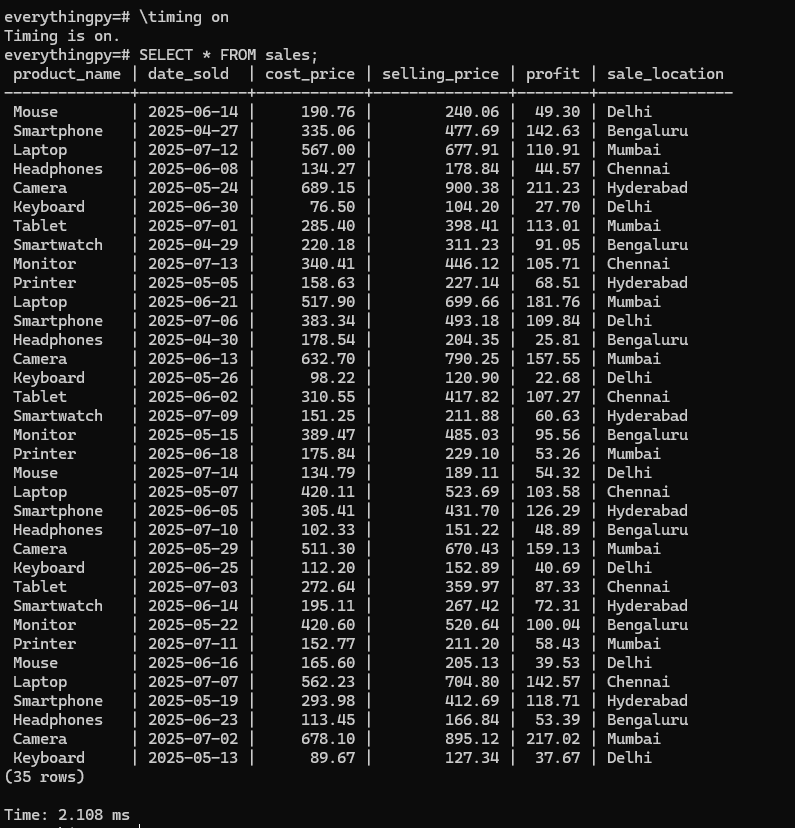

First, I’ll create a table called “sales” with the following columns - product_name, date_sold, cost_price, selling_price, profit, sales_location. I’ve also added 35 products sold as entries to work on.

Now let’s say I want to find out what the net profit was in Hyderabad overall, across products and dates.

It’s been a while since I wrote free-hand SQL, so I actually thought of two queries in the process of writing them :

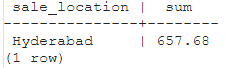

SELECT sale_location, SUM(profit) FROM sales WHERE sale_location = 'Hyderabad' GROUP BY sale_location;

and

SELECT SUM(profit) AS net_profit_hyderabad FROM sales WHERE sale_location = 'Hyderabad';

and both turned out to work fine, except the former returned :

and the latter returned

I thought about why I used GROUP BY involuntarily, when it wasn’t needed actually and looked it up.

Every non-aggregated item that appears in

SELECT,ORDER BY, orHAVINGmust be listed inGROUP BY.

I had accidentally done the right thing but had forgotten why I was doing it. Since “sales_location” is a non-aggregated item i.e. I am not “summing” by sales_location, I should GROUP BY that column - which I had done.

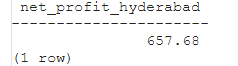

Anyway, let’s see how long each of these statements takes -

First I will enable timing on this editor using

\timing on

in psql.

Now let’s look at how long the other queries take -

If you’re following along, you will see that the table ‘sales’ has 35 records - not too big.

So statements take the following time :

SELECT * FROM sales; 1.784 msSELECT * FROM sales WHERE sale_location = 'hyderabad'; 1.737 msSELECT SUM(profit) FROM sales where sale_location = 'Hyderabad' ; 3.805 msSELECT sale_location, SUM(profit) from sales where sale_location = 'Hyderabad' GROUP BY sale_location; 1.651 ms

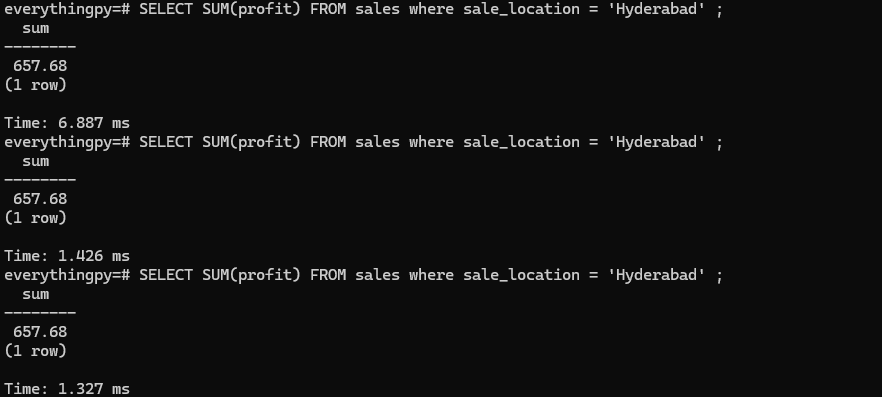

Repeating the 3rd query 3 more times just to convince ourselves that the increased time is not due to the query itself or because of the query plan created for it -

It is surprisingly hard to obtain accurate and precise measurements of the time spent executing a query, because there are many sources of variance... Even after taking proactive steps to improve the measurements, they still vary quite a lot.

Now, let me add an Index on the sale_location column, since that is the column I want to perform a look up by -

As shown above, an index can be created using the command -

CREATE INDEX idx_sale_location ON sales(sale_location);Where idx_sale_location is the name of the index I want to create, sales is the table I want to create it on and sale_location is the column I want to index by.

Now let’s recheck the time taken for each of the above SELECT commands to see if our index took effect!

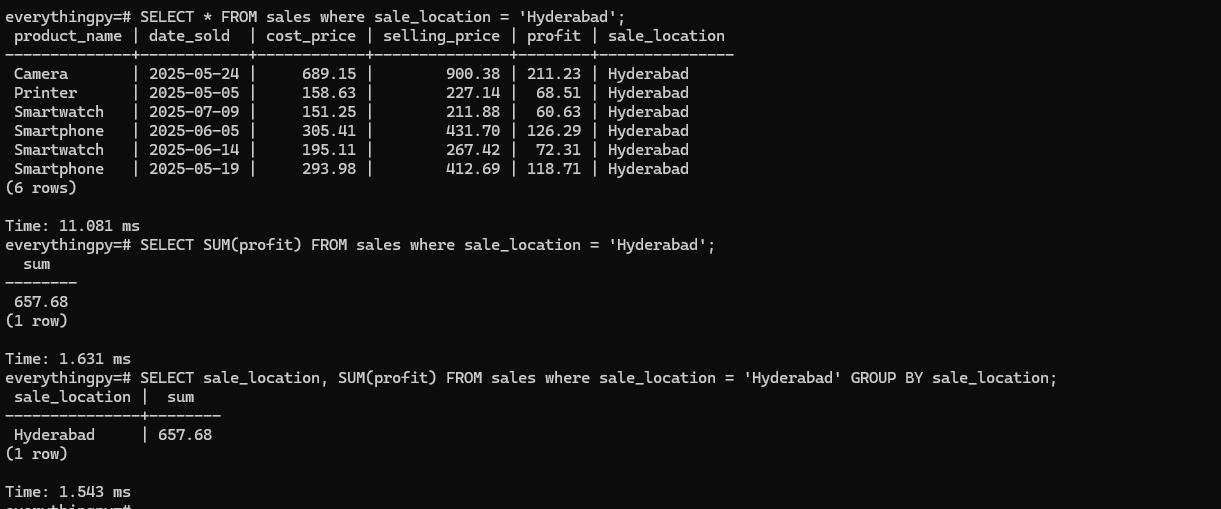

Now,

SELECT * FROM sales WHERE sale_location = 'hyderabad'; 11.081 ms

SELECT SUM(profit) FROM sales where sale_location = 'Hyderabad' ; 1.631 msSELECT sale_location, SUM(profit) from sales where sale_location = 'Hyderabad' GROUP BY sale_location; 1.543 ms

While it may Seem that the second and third queries have sped up from before, that’s actually not true. It’s simply a luck of the draw in terms of the amount of resources being used at the time of this execution and other factors that have nothing to do with the Index at all. In fact, if you look at query 1, the fact that it seems as if it took 10 ms MORE than before seems rather counterintuitive!

So how do we confirm if the Index was actually used?

As you can see, using the EXPLAIN command, we can ascertain whether the SELECT queries made use of the Index or not to prepare their query plan and fetch the results - which in this case looks like it did not.

This is a direct function of the size of the table itself. For 35 records, it’s far too trivial a usecase for the index to be used.

So at what point does the camel’s back break? When do the indices kick in?

We’ll both find out together in the next edition of EverythingPostgres - Yes, that’s what we’re calling it now :D

Also check out my Youtube channel from above and Subscribe. I hope to create more videos on all things Engineering - From coding in Python to Databases and GenAI !